Guadalupe River (Texas)

| Guadalupe River Río Guadalupe | |

|---|---|

A bluff at Guadalupe River State Park | |

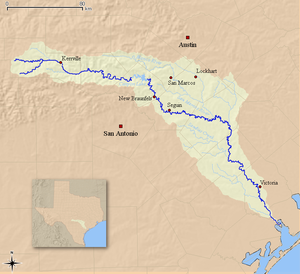

Map of the Guadalupe River watershed | |

| |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| Region | Texas Hill Country, Texas Coastal Bend |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Kerr County, Texas |

| • coordinates | 30°05′17″N 99°38′32″W / 30.08806°N 99.64222°W |

| • elevation | 676 m (2,218 ft) |

| Mouth | San Antonio Bay, Gulf of Mexico |

• coordinates | 28°24′07″N 96°46′57″W / 28.40194°N 96.78250°W |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 370 km (230 mi) |

| Basin size | 17,353 km2 (6,700 sq mi)[1] |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 34 m3/s (1,200 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Rebecca Creek[2] |

| • right | Turtle Creek[3] |

The Guadalupe River (/ˌɡwɑːdəˈlup/)[4] (Spanish pronunciation: [gwaðaˈlupe]) runs from Kerr County, Texas, to San Antonio Bay on the Gulf of Mexico, with an average temperature of 17.75 degrees Celsius (63.95 degrees Fahrenheit).[5] It is a popular destination for rafting, fly fishing, and canoeing. Larger cities along it include Kerrville, New Braunfels, Seguin, Gonzales, Cuero, and Victoria. It has several dams along its length, the most notable of which, Canyon Dam, forms Canyon Lake northwest of New Braunfels.

Course

[edit]The upper part, in the Texas Hill Country, is a smaller, faster stream with limestone banks and shaded by pecan and bald cypress trees. It is formed by two main tributary forks, the North Fork and South Fork Guadalupe Rivers.[6][7] It is popular as a tubing destination where recreational users often float down it on inflated tire inner tubes during the spring and summer months. East of Boerne, on the border of Kendall County and Comal County, it flows through Guadalupe River State Park, one of the more popular tubing areas along it.

The lower part begins at the outlet of Canyon Lake, near New Braunfels. The section between Canyon Dam and New Braunfels is the most heavily used in terms of recreation. It is a popular destination for whitewater rafters, canoeists, kayakers, and tubing. When the water is flowing at less than 1,000 cu ft/s (28 m3/s) there could be hundreds if not thousands of tubes on this stretch of it. At flows greater than 1,000 cu ft/s (28 m3/s), there should be very few tubes on the water. Flows greater than 1,000 cu ft/s (28 m3/s) and less than 2,500 cu ft/s (71 m3/s) are ideal for rafting and paddling. The flow is controlled by Canyon Dam, and by the amount of rainfall the area has received. It is joined by the Comal River in New Braunfels and the San Marcos River about two miles (3 km) west of Gonzales. The part below the San Marcos River, as well as the latter, is part of the course for the Texas Water Safari.

The San Antonio River flows into it just north of Tivoli. Ahead of the entry into the San Antonio Bay estuary, it forms a delta and splits into two distributaries referred respectively as the North and South parts. Each distributary flows into the San Antonio Bay estuary at Guadalupe Bay.[8][9]

-

The Guadalupe River in Kerr County, Texas, USA (8 May 2014).

-

The Guadalupe River in Gruene

-

The Guadalupe River near Hunt

-

The Guadalupe River under Interstate 35 in New Braunfels

-

Mouth of the South Guadalupe River at Guadalupe Bay

History

[edit]The river was first called after Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe by Alonso de León in 1689. It was renamed the San Augustin by Domingo Terán de los Ríos who maintained a colony on it, but the name Guadalupe persisted. Many explorers referred to the current Guadalupe as the San Ybón above its confluence with the Comal, and instead the Comal was called the Guadalupe. Evidence indicates that it has been home to humans for several thousand years, including the Karankawa, Tonkawa, and Huaco (pronounced like Waco) Indians.

Being led by Prince Solms, 228 pioneer immigrants from Germany traveled overland from Indianola to the site chosen to be the first German settlement in Texas, New Braunfels. Upon reaching the river, the pioneers found it too high to cross due to the winter rains. Prince Solms, perhaps wishing to impress the others with his bravado, plunged into the raging waters and crossed the swollen river on horseback. Not to be outdone by anyone, Betty Holekamp immediately followed and successfully crossed the river.[10] Thus Betty Holekamp is known as the first white woman to cross the Guadalupe on horseback.

1987 flood

[edit]On July 17, 1987, a sudden flash flood swept a bus full of children away at a low water crossing. The incident occurred near the town of Comfort, Texas, which lies about 50 miles (80 km) northwest of San Antonio. At the time, the Pot O' Gold Ranch, which is situated on the south side of the river about two miles southwest of Comfort, was hosting a church camp, with over 300 children from various churches attending. On the night of July 16 and into the morning of the 17th, almost 12 inches (300 mm) of rain had fallen across the Texas hill country to the north, triggering immense flooding on the Guadalupe River. The camp was scheduled to end on the 17th and the children were to be headed home later that day, but camp supervisors at the ranch decided to evacuate the children early that morning before it rose too high. At around 9 am that morning, the children were loaded into buses and the buses were directed to a low water crossing.

While most of the buses managed to make it across, one bus from the Seagoville Road Baptist Church/Balch Springs Christian Academy in the Dallas suburb of Balch Springs was swept away, along with Pastor Richard Koons, his wife Lavonda, chaperons Allen and Deborah Coalson, and thirty-nine children, ranging in age from 8 to 17. The vehicle had been among the last to leave the camp and proceed alongside the flooded crossing, but when the bus stalled due to rapidly rising waters, Koons and Coalson attempted to get the children to safety by instructing them to form a human chain so that they could reach shore hand in hand. As this was attempted, a sudden rush of water broke the chain and swept them all away. Rescuers from the Texas Department of Public Safety and the US Army's 507th Medical Division managed to save all four adults and twenty-nine of the children via helicopters. The last survivor was rescued from the river around 11:30 am, and by that afternoon two children had been confirmed dead, with eight still missing. The first confirmed fatality was 14-year-old Melanie Finley, who after being lifted from the river by helicopter lost her grip on the rope and fell to her death. The second fatality was thirteen-year-old Tonya Smith, who was found entangled in barbed wire two miles downstream from where the bus was washed away.[11] Several parents of the children descended on Comfort, most staying at a makeshift shelter set up by town residents and the American Red Cross at the Comfort Elementary School. Six more bodies were recovered from the river on July 18, identified as Lagenia Keenum, 15; Michael Lane, 16;[12] Michael O'Neal, 16; Cindy Sewell, 16; Christopher Sewell, 13; and Stacey Smith, 16 (Sister of Tonya Smith). The following day, the ninth and final body was recovered from the river, identified as 14-year-old Leslie Gossett. The body of 17-year-old John Bankston Jr., the oldest of the ten victims, was never found.[13]

In the summer of 1988, near the edge of the river and at the foot of the driveway to the Pot O' Gold Ranch, a memorial plaque was dedicated to the children who died as well as those who survived. On April 18, 1989, the story of the deaths and rescues was shown as the pilot episode of Rescue 911, and in 1993 was made into a television movie called The Flood: Who Will Save Our Children? The film followed the experiences of some of the children and their families, and starred Joe Spano as Reverend Richard Koons.

River conditions

[edit]The river's conditions can change rapidly. Its flow is set by the dam at Canyon Lake and operated by the Army Corps of Engineers. It is highly regulated and well maintained to ensure safety. It is, however, prone to severe flooding. During the rainy seasons the water can reach well above the banks and exceed "normal" levels, in which case it can become life threateningly dangerous due to swift currents. If the flow gauge exceeds 1,000 cubic feet per second (28 m3/s) at the Sattler Gage, it is generally considered by local authorities as too dangerous for recreational purposes for all except expert kayakers and/or whitewater rafters. On October 31, 2013, the part in New Braunfels rose from 74 to 33,500 cubic feet per second (2.1 to 948.6 m3/s) in one hour and fifteen minutes due to locally heavy rainfall.

Uses

[edit]Fly fishing for rainbow, and brown trout below Canyon Lake is extremely popular along the entire river, anglers can catch guadalupe bass, largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, rio grande cichlid, striped bass and white bass. Tailrace fishing is also common below many of the weirs, spillways and dams such as West-point Pepperell Dam located on the north end of Lake Dunlap within the City Limits of New Braunfels.

The Mandaean-American community of San Antonio regularly performs masbuta (baptism) rituals in the Guadalupe River.[14]

Points of interest

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ http://www.swd.usace.army.mil/Portals/42/docs/civilworks/Fact%20Sheets/Fort%20Worth/FY13%20Guadalupe%20San%20Antonio%20River%20Basin,%20TX.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Guadalupe River (Texas)

- ^ Turtle Creek (Kerr County) from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- ^ https://texasalmanac.com/sites/default/files/images/topics/TownPronunciationGuide.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Roddy, W. R.; Wadded, Kidd M. (1982). "Water Quality Of Canyon Lake Central Texas" (PDF). U.S. Department of the Interior. p. 21. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: North Fork Guadalupe River

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: South Fork Guadalupe River

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: North Guadalupe River

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: South Guadalupe River

- ^ Ransleben, Guido E.; A Hundred Years of Comfort in Texas; 1954

- ^ "Raging River Kills 2 8 Missing In Texas Tragedy". Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "Archives - Philly.com". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "Get Top Local News". News Radio 1200 WOAI. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ Busch, Matthew; Ross, Robyn (18 February 2020). "Against The Current". Texas Observer. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

External links

[edit]- Guadalupe River from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Edwards Aquifer

- Canyon Lake Chamber of Commerce

- TPWD Palmetto State Park

- TPWD Guadalupe State Park

- Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority, Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority: Flow and Lake Data, archived from the original on 2008-06-02, retrieved 2008-05-24

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Guadalupe River

- Guadalupe River (Texas)

- Rivers of Texas

- Texas Hill Country

- Rivers of Comal County, Texas

- Rivers of Kerr County, Texas

- Rivers of Kendall County, Texas

- Rivers of Guadalupe County, Texas

- New Braunfels, Texas

- Rivers of Gonzales County, Texas

- Rivers of DeWitt County, Texas

- Rivers of Victoria County, Texas

- Rivers of Calhoun County, Texas

- Rivers of Refugio County, Texas

- Rivers in Mandaeism